Hi, I am Gregor Hohpe, co-author of the book Enterprise Integration Patterns. I work on and write about asynchronous messaging systems, distributed architectures, and all sorts of enterprise

computing and architecture topics.

Hi, I am Gregor Hohpe, co-author of the book Enterprise Integration Patterns. I work on and write about asynchronous messaging systems, distributed architectures, and all sorts of enterprise

computing and architecture topics.

Find my posts on IT strategy, enterprise architecture, and digital transformation at ArchitectElevator.com.

Part of my job is to review system architectures. So I frequently ask teams to show me "their architecture", but almost as frequently I don't consider what I receive an architecture document. The inevitable question "what do you expect?" is also not so easy for me to answer: despite many formal definitions it's not immediately clear what architecture is or whether a document really depicts an architecture. Too often we have to fall back to the "I know it when I see it" test famously applied to obscene material by the Supreme Court. We'd hope that identifying architecture is a more noble task than identifying obscene material, so let's try a little harder. I am not a big believer in all-encompassing definitions, but tend to use lists of defining characteristics or tests that can be applied. One of my favorite tests for architecture documentation is whether it contains any non-trivial decisions and the rationale behind them.

Enough attempts at defining software architecture have been made that the Software Engineering Institute maintains a reference page of architecture definitions.

The most widely used definitions are likely the one from Garlan and Perry from 1995:

The structure of the components of a system, their interrelationships, and principles and guidelines governing their design and evolution over timethe ANSI/IEEE Std 1471 version from 2000 (adopted as ISO/IEC 42010 in 2007):

The fundamental organization of a system, embodied in its components, their relationships to each other and the environment, and the principles governing its design and evolutionand the TOGAF variation thereof:

The structure of the components, their interrelationships, and principles and guidelines governing their design and evolution over timeOne of my personal favorites is from Desmond D'Souza's and Alan Cameron Wills' book Objects, Components, and Frameworks with UML: The Catalysis(SM) Approach (1998):

Design decisions about any system that keep implementors and maintainers from exercising needless creativityThe key point here is not that architecture should dampen all creativity, but needless creativity, of which I witness ample amounts. I also like the mention of decisions. Decision-making is a big part of what an architect does and that's why I like books like Ron Howard's Foundations of Decision Analysis and Coursera courses like Scott Page's Model Thinking.

Despite these well-thought-out definitions, it's not easy to apply them when someone walks up with a PowerPoint slide showing boxes and lines and claims "this is the architecture of my system". The first test I tend to apply is whether the documentation contains meaningful decisions. After all, if no decisions need to be made, why do we need an architect and architectural documentation?

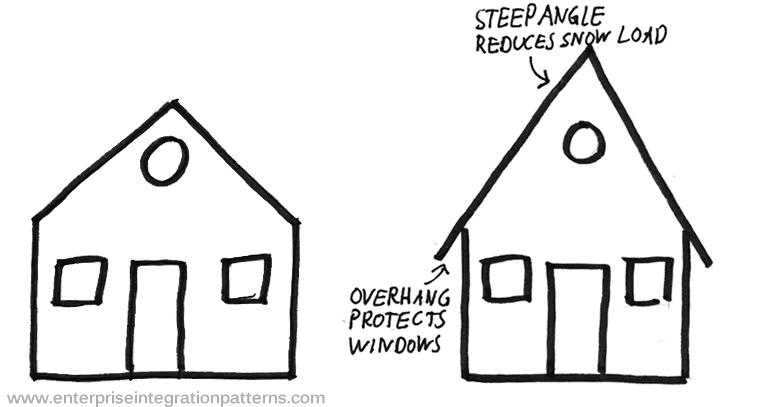

I am a big fan of Martin Fowler's knack for explaining the essence of things using extremely simple examples. This motivated me to illustrate the "architectural decision test" with the simplest example I could think of, drawing from the (admittedly limping) analogy to building architecture. I even took it upon myself to supply the artwork to make sure things end up about as basic as one could wish for and to pay homage to Alexander's Pattern Sketches:

Let's look at the drawing of a house on the left. It has many of the elements that we desire in the popular definitions of systems architecture: we see the main components of the system (door, windows, roof) and their interrelationships (door and windows in the wall, roof on the top). We might be a tad thin, though, on principles governing its design, but we do notice that we have a single door that reaches the ground and multiple windows, which follows common building principles.

Yet, to build such a house I would not want to pay an architect. To me this house is "cookie-cutter", meaning I don't see any non-obvious decisions that an architect would have made. Consequently, I would not consider this architecture.

Let's compare this to the sketch on the right-hand side. The sketch is equally simple and poorly drawn and the house is almost the same, except for the roof. This house has a steep roof and for a good reason: the house is designed for a cold climate where winters bring extensive snowfall. Snow is quite heavy and can easily overload the roof of the house. A steep roof allows the snow to slide off or be easily removed thanks to gravity, a pretty cheap and widely available resource. Additionally, an overhang prevents the sliding snow from piling up right in front of the windows.

To me, this is architecture: non-trivial decisions have been made and documented. The decisions are driven by the system context, in this case the climate. The documentation highlights the decisions and omits unnecessary noise.

If you believe these architectural decisions were all too obvious, let's look at a very different house:

This house looks very different because it was designed for a very different climate: a hot and sunny one. This allows the walls to be made out of glass as insulation against low temperatures is less of a concern. However, walls of glass have the problem that the sun heats up the building making it feel more like a greenhouse. A flat roof is no problem in this climate, so extending the roof well beyond the glass walls provides shade in the hot summer when the sun is high in the sky. In the winter, when the sun is low on the horizon, the sun reaches through the windows and helps warm the building interior. Again, we see a fairly simple, but fundamental architectural decision documented in an easy-to-understand format that highlights the essence of the decision and the rationale behind it.

If you think the idea of building an overhanging roof is not all that original or significant, try buying one of the first homes to feature such a design, e.g. the Case Study House No 22 in Los Angeles by architect Pierre Koenig. It's easily in the league for the most recognized residential building in Los Angeles or beyond (aided by Julius Shulman's iconic photograph) and is obviously not for sale. No one is perfect, though: UCLA PhD students have measured that the overhang works better on the south-facing facade than west or east.

The simple house example also highlights another important property of architectures: rarely is an architecture simply "good" or "bad". Rather, architecture tends to be fit or unfit for purpose. A house with glass walls and a flat roof may be regarded as great architecture, but probably not in the Swiss Alps where it'll collapse after a few winters or get a leaking roof. Even the dreaded Big Ball of Mud has its place in "fit for purpose" architectures, e.g. when you need to make a deadline at all cost and can't care much about what happens afterwards. This may not be the context you wish for, but just like houses in some regions have to be earthquake proof, some architectures have to be management-proof.

Having stretched the overused building architecture analogy one more time, how do we translate this back to software systems architecture? Systems architecture does not have to be something terribly complicated. It must include, however, significant decisions that are documented and are based on a clear rationale. The word "significant" may be open to some interpretation and depend on the level of sophistication of the organization, but "we separate front-end from back-end code", "we use monitoring", or "migrating systems is risky" surely have the ring of "my door reaches the ground so people can walk in" or "I put windows in the walls so light can enter". Instead, when discussing architectures let's talk about what is not obvious or something that involved heavy trade-offs. For example, "do you use a service layer and why?" (some people may find even this obvious) or "why do you use a session-oriented conversation protocol?"

It's quite amazing how many "architecture documents" do not pass this relatively simple test. I hope using the building analogy provides a simple and non-threatening way to provide feedback and to motivate architects to better document their designs and decisions.

I am looking for top-notch Cloud Infrastructure Architects and Principal Software Architects for my team. We are building a private cloud infrastructure for one of the largest

insurance companies in the world and re-architect critical core applications to efficiently

run on it. You'll be working in a highly motivated team of technical experts who understand

what architecture is.

I am looking for top-notch Cloud Infrastructure Architects and Principal Software Architects for my team. We are building a private cloud infrastructure for one of the largest

insurance companies in the world and re-architect critical core applications to efficiently

run on it. You'll be working in a highly motivated team of technical experts who understand

what architecture is.